Giacomo Balla *

(Turin 1871–1958 Rome)

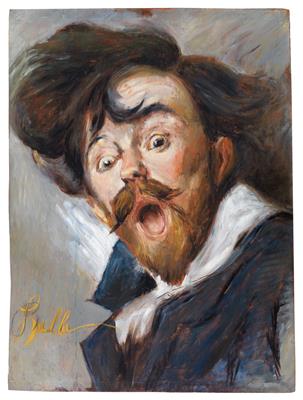

Autosmorfia, 1900, signed Balla, oil on wood panel, 42.2 x 31.2 cm

Photo certificate:

Elena Gigli, Rome, no. 827, 2018

Provenance:

Atelier of the artist, Rome

E. Coppola Collection, Rome (handwritten on the reverse: proprietà Coppola), acquired from the artist’s atelier in 1968 and thence by inheritance

Private Collection, Italy

Exhibited:

Rome, Balla pre-futurista, Galleria dell’Obelisco, January/February 1968,

exh. cat. p. 12, no. 4 with ill. (with wrong dimensions)

Literature:

Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, Balla pre-futurista, Bulzoni ed., Rome 1968,

p. 39, no. 15, p. 12 with ill.

Teresa Fiori, Archivi del Divisionismo, De Luca ed., Rome 1969, vol. II,

no. X.22, pl. 1710 with ill.

Elica Balla, Con Balla, Multipla ed., Milan 1984, vol. I, p. 32 with ill.

The painter before the mirror

The interest in the psyche of the subject, which in the sixteenth century was culturally rooted in the pseudo-scientific thought of the era, based on magical, alchemical, and physiognomic elements, took a decisively more modern, rational, and scientific turn in the seventeenth century. The study of this rationality and of the movements of the human spirit thus began to characterise numerous portraits and self-portraits of the era. Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s work provides an eloquent example of this and demonstrates notable immediacy and effective psychological introspection. Interior investigation and autobiographical reflection are also central elements in the work of European artists, particularly that of Rembrandt. On a par with Dürer, he tenaciously dedicated himself to self-portraiture, leaving forty-six self-portraits, both drawn and painted, which condense all the strands typical of sixteenth-century production. It was these very targeted, introspective self-portraits that conveyed Rembrandt’s growing suffering onto canvas, which lent him the intuition to work out his progressive disintegration in his brushstrokes and the material substance which progressively erased the traces of the bright, sharp precision of the paintings of his youth. It was this stylistic path that elicited the wonder of his contemporaries and whose sole precedent was Titian’s “non finito” (unfinished) works. Rembrandt’s research draws the period of experimentation and classification of the self-portrait to a close, a period which lasted approximately from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century, and which conferred the genre with importance and autonomy within the European artistic tradition.

In the eighteenth century, we find an important meeting point of art and psychology in the so-called “Character heads” of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt (1736-1783), defined by Rudolf Wittkower as the “test bed for the study of problems relating to artists and insanity.” This is an almost unique case within the history of art, with a single precedent in the aforementioned Bernini who created two character heads for Cardinal Foix De Montoya in 1619 titled “The Blessed Soul” and “The Damned Soul”. If Bernini’s intent was to study human character and passions, Messerschmidt conveys the figure of a saturnine artist, extravagant and fatally absorbed in an individualistic and unshareable representation of reality, of himself, and of his art. Among the artists of the nineteenth century we find various attempts to present the self-portrait in an organic context within the artist’s own career, so that the images of self and art coincide perfectly. Gustave Courbet’s (1844-49) The Desperate Man, Self-portrait, appears to convey surprised awareness of his own appearance through the apparent reflection of his image in the mirror, with quasi-hyperrealist precision. It was psychoanalysis, developed by Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) in the early years of the twentieth century, that was to give rise to an Oedipal turn in art, with subjective pictorial experiments which drew on regressive dreams and erotic fantasies, as appears evident in the work of Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele and Oscar Kokoschka. Vienna at that time did not tolerate such experiments as they suggested a crisis in the stability of the self and of social institutions, a crisis which Freud was quick to analyse, and which enveloped more than just the Austrian capital alone. Early twentieth-century Italy also saw the birth of a more “human and genuine” art, particularly in the so-called “little Roman avant-garde” (Cena, Pellizza da Volpedo, Balla, Prini), inspired by present reality and with a fundamental idealism tinged with sentimental and psychological accents, and a very intense humanitarian charge. This is the period in which Balla experimented with his “grimace” with its large tuft of red hair and bohemian neckerchief. It is 1900, the year of the Paris Universal Exposition. The “City of Light” is more scintillating than ever. The young Giacomo Balla is 29 years old, and in Paris since September, guest of the artist Serafino Macchiati. “Let us try again...I go to Paris. There, there will be great art, and one can learn from the great masters,” the painter wrote to Elisa, his wife. He visited the Louvre, where, among the canvases of the Old Masters, he also came across the self-portrait of the Dutch artist Adrien Brouwer and La haine et la folie by Vucetic. Writing once again to Elisa: “(...) After breakfast, I continued to paint heads pulling the most extravagant grimaces (they are SELF-GRIMACES), I will do several, and then attempt to sell them.”

The “self-grimace” (Autosmorfia) is an image in motion which anticipates later experimental analysis such as the girl running on the balcony, the flight of the swallows or the speed of the car. But it is also something different, already attempted in a series of self-portraits (the first done on the back of an earlier photo of himself) which, from 1894 on, explore the expressive potential of the human face.

As is the case with other contemporary Italian artists painting self-portraits, Balla is also interested in the issue of communicating what it is he decides to be: truth or lie, joy, or the visualisation of fears and hidden obsessions. The myth of Narcissus teaches us that one can be absolute fiction or unconscious truth, and that on the psychoanalytical canvas the modern artist distinguishes himself from his predecessors through turning down eternity in favour of consciousness and aspiring to know himself through self-portraiture.

Expert: Maria Cristina Corsini

Maria Cristina Corsini

Maria Cristina Corsini

+39-06-699 23 671

maria.corsini@dorotheum.it

04.06.2019 - 17:00

- Dosažená cena: **

-

EUR 75.300,-

- Odhadní cena:

-

EUR 80.000,- do EUR 120.000,-

Giacomo Balla *

(Turin 1871–1958 Rome)

Autosmorfia, 1900, signed Balla, oil on wood panel, 42.2 x 31.2 cm

Photo certificate:

Elena Gigli, Rome, no. 827, 2018

Provenance:

Atelier of the artist, Rome

E. Coppola Collection, Rome (handwritten on the reverse: proprietà Coppola), acquired from the artist’s atelier in 1968 and thence by inheritance

Private Collection, Italy

Exhibited:

Rome, Balla pre-futurista, Galleria dell’Obelisco, January/February 1968,

exh. cat. p. 12, no. 4 with ill. (with wrong dimensions)

Literature:

Maurizio Fagiolo dell’Arco, Balla pre-futurista, Bulzoni ed., Rome 1968,

p. 39, no. 15, p. 12 with ill.

Teresa Fiori, Archivi del Divisionismo, De Luca ed., Rome 1969, vol. II,

no. X.22, pl. 1710 with ill.

Elica Balla, Con Balla, Multipla ed., Milan 1984, vol. I, p. 32 with ill.

The painter before the mirror

The interest in the psyche of the subject, which in the sixteenth century was culturally rooted in the pseudo-scientific thought of the era, based on magical, alchemical, and physiognomic elements, took a decisively more modern, rational, and scientific turn in the seventeenth century. The study of this rationality and of the movements of the human spirit thus began to characterise numerous portraits and self-portraits of the era. Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s work provides an eloquent example of this and demonstrates notable immediacy and effective psychological introspection. Interior investigation and autobiographical reflection are also central elements in the work of European artists, particularly that of Rembrandt. On a par with Dürer, he tenaciously dedicated himself to self-portraiture, leaving forty-six self-portraits, both drawn and painted, which condense all the strands typical of sixteenth-century production. It was these very targeted, introspective self-portraits that conveyed Rembrandt’s growing suffering onto canvas, which lent him the intuition to work out his progressive disintegration in his brushstrokes and the material substance which progressively erased the traces of the bright, sharp precision of the paintings of his youth. It was this stylistic path that elicited the wonder of his contemporaries and whose sole precedent was Titian’s “non finito” (unfinished) works. Rembrandt’s research draws the period of experimentation and classification of the self-portrait to a close, a period which lasted approximately from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century, and which conferred the genre with importance and autonomy within the European artistic tradition.

In the eighteenth century, we find an important meeting point of art and psychology in the so-called “Character heads” of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt (1736-1783), defined by Rudolf Wittkower as the “test bed for the study of problems relating to artists and insanity.” This is an almost unique case within the history of art, with a single precedent in the aforementioned Bernini who created two character heads for Cardinal Foix De Montoya in 1619 titled “The Blessed Soul” and “The Damned Soul”. If Bernini’s intent was to study human character and passions, Messerschmidt conveys the figure of a saturnine artist, extravagant and fatally absorbed in an individualistic and unshareable representation of reality, of himself, and of his art. Among the artists of the nineteenth century we find various attempts to present the self-portrait in an organic context within the artist’s own career, so that the images of self and art coincide perfectly. Gustave Courbet’s (1844-49) The Desperate Man, Self-portrait, appears to convey surprised awareness of his own appearance through the apparent reflection of his image in the mirror, with quasi-hyperrealist precision. It was psychoanalysis, developed by Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) in the early years of the twentieth century, that was to give rise to an Oedipal turn in art, with subjective pictorial experiments which drew on regressive dreams and erotic fantasies, as appears evident in the work of Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele and Oscar Kokoschka. Vienna at that time did not tolerate such experiments as they suggested a crisis in the stability of the self and of social institutions, a crisis which Freud was quick to analyse, and which enveloped more than just the Austrian capital alone. Early twentieth-century Italy also saw the birth of a more “human and genuine” art, particularly in the so-called “little Roman avant-garde” (Cena, Pellizza da Volpedo, Balla, Prini), inspired by present reality and with a fundamental idealism tinged with sentimental and psychological accents, and a very intense humanitarian charge. This is the period in which Balla experimented with his “grimace” with its large tuft of red hair and bohemian neckerchief. It is 1900, the year of the Paris Universal Exposition. The “City of Light” is more scintillating than ever. The young Giacomo Balla is 29 years old, and in Paris since September, guest of the artist Serafino Macchiati. “Let us try again...I go to Paris. There, there will be great art, and one can learn from the great masters,” the painter wrote to Elisa, his wife. He visited the Louvre, where, among the canvases of the Old Masters, he also came across the self-portrait of the Dutch artist Adrien Brouwer and La haine et la folie by Vucetic. Writing once again to Elisa: “(...) After breakfast, I continued to paint heads pulling the most extravagant grimaces (they are SELF-GRIMACES), I will do several, and then attempt to sell them.”

The “self-grimace” (Autosmorfia) is an image in motion which anticipates later experimental analysis such as the girl running on the balcony, the flight of the swallows or the speed of the car. But it is also something different, already attempted in a series of self-portraits (the first done on the back of an earlier photo of himself) which, from 1894 on, explore the expressive potential of the human face.

As is the case with other contemporary Italian artists painting self-portraits, Balla is also interested in the issue of communicating what it is he decides to be: truth or lie, joy, or the visualisation of fears and hidden obsessions. The myth of Narcissus teaches us that one can be absolute fiction or unconscious truth, and that on the psychoanalytical canvas the modern artist distinguishes himself from his predecessors through turning down eternity in favour of consciousness and aspiring to know himself through self-portraiture.

Expert: Maria Cristina Corsini

Maria Cristina Corsini

Maria Cristina Corsini

+39-06-699 23 671

maria.corsini@dorotheum.it

|

Horká linka kupujících

Po-Pá: 10.00 - 17.00

kundendienst@dorotheum.at +43 1 515 60 200 |

| Aukce: | Modern Art |

| Typ aukce: | Salónní aukce |

| Datum: | 04.06.2019 - 17:00 |

| Místo konání aukce: | Wien | Palais Dorotheum |

| Prohlídka: | 25.05. - 04.06.2019 |

** Kupní cena vč. poplatku kupujícího a DPH

Není již možné podávat příkazy ke koupi přes internet. Aukce se právě připravuje resp. byla již uskutečněna.

Všechny objekty umělce