Egon Schiele

(Tulln 1890–1918 Vienna)

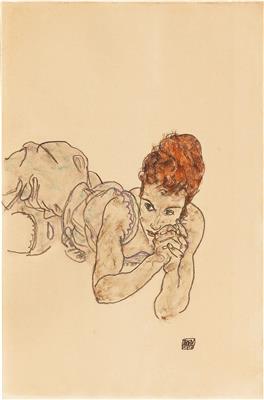

Liegende Frau, signed, dated Egon Schiele 1917, gouache and black crayon on paper, sheet size 45 x 29.7 cm, framed

Jane Kallir, Egon Schiele: The Complete Works, New York 1990, p. 582, No. D. 1998, with ill.

Jane Kallir, Egon Schiele: The Complete Works, New York 1998, p. 582, No. D. 1998, with ill.

Provenance:

Private Collection, Salzburg, since the early 1930s

TEXT BY JANE KALLIR

© Jane Kallir

EGON SCHIELE’S LAST YEARS, 1917-18

In early 1917, Egon Schiele returned to Vienna from Mühling, the rural outpost where he had been stationed with the Austrian Army. During the preceding year of military service, he had produced relatively little art, but now he approached his career with renewed vigor. He rapidly reestablished and expanded his art-world contacts, fostering a relationship with the young director of the Staatsgalerie, Franz Martin Haberditzl, that led to a portrait commission (Kallir P. 309) and, in 1918, to the museum’s acquisition of the oil Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, Seated (Kallir P. 316). The publication in mid-1917 of a portfolio of facsimile reproductions of Schiele drawings, accompanied by a set of postcards, introduced his work to a new, broader audience. The artist began receiving fan mail and unsolicited inquiries from collectors, editors and writers. Exhibition activities picked up the pace, and Schiele was often asked not just to participate, but to organize these ventures. For the first time, he could afford to hire a contingent of professional models. By 1918, he also needed a secretary.

In keeping with his burgeoning professional life, Schiele created a large number of drawings in the last two years of his life: studies for portrait commissions and studies of various models. His 1917-18 style diverged sharply from the Expressionist idiom that had characterized his work prior to his induction into the army in 1915. The solipsistic self-absorption of late adolescence had been tempered by the artist’s marriage, also in 1915, to Edith Harms and by his empathy for the prisoners of war whom he encountered as a soldier. Complementing this more humanistic approach, Schiele’s drawings had become far more conventionally realistic. The contours hewed almost exclusively to the requirements of representational accuracy, with little latitude for expressive deviation. His palette was more subdued and naturalistic. A thin brownish under-glaze defined the principal volumes, and bolder dabs of color were used to highlight inflection points such as elbows, knuckles or lips. More opaque solids (stockings or hair) set off luminous drapery and flesh.

Overall Schiele was less concerned with color than with volume and shape, and increasingly he was driven to explore his subjects through drawing alone.

In 1917, for the first time in his brief life, Egon Schiele had access to a great many models. He was no longer compelled to enlist family, friends and girlfriends, but could afford to hire a changing retinue of professionals. Unsurprisingly, Edith Schiele objected, jealous of the naked women who populated her husband’s studio. But while she wanted to be his only model, this demand was complicated by Edith’s reluctance to pose nude. To assuage her embarrassment, Egon promised to alter her features so that she would not be recognized. And this may be one reason why the artist’s wife can be conclusively identified in relatively few of his more erotic works.

Edith’s jealously notwithstanding, she was clearly not Schiele’s only, or indeed even his principal model in 1917. In addition to a large contingent of professionals, Edith’s sister Adele Harms proved more than willing to pose. Like Edith, Adele seems seldom to have stripped completely. When not fully clothed, both sisters are usually depicted in flimsy chemises. In Schiele’s conventional portraits of the sisters, their faces are readily distinguished: Edith has more delicate features and a wistful sweetness; Adele’s visage is square-jawed and coarser. However, Adele is no easier to identify than Edith in the artist’s figure studies.

Schiele’s formal portraits of women had become far more incisive since his marriage in 1915, but his depictions of the nude or semi-nude female had grown more impersonal. The latter drawings were often intended as studies for allegorical paintings. As such, the artist was less interested in faces than in poses. His stylized simplification of facial features can make it difficult to distinguish the subjects of his figure drawings. Further complicating matters, in the case of Adele and Edith, is their family resemblance, and the fact that Schiele was not always accurate in his replication of telling details. (Adele had dark hair, while Edith was blond, but either might be depicted with reddish tresses.)

For all the foregoing reasons, it is impossible to conclusively identify the subject of Liegende Frau. Her facial features look somewhat like those of both Adele and Edith. She might be either sister, or neither. A similar face appears in several other works from the period (see Kallir D. 1977-80).

21.11.2017 - 18:00

- Dosažená cena: **

-

EUR 2.345.000,-

- Odhadní cena:

-

EUR 700.000,- do EUR 1.200.000,-

Egon Schiele

(Tulln 1890–1918 Vienna)

Liegende Frau, signed, dated Egon Schiele 1917, gouache and black crayon on paper, sheet size 45 x 29.7 cm, framed

Jane Kallir, Egon Schiele: The Complete Works, New York 1990, p. 582, No. D. 1998, with ill.

Jane Kallir, Egon Schiele: The Complete Works, New York 1998, p. 582, No. D. 1998, with ill.

Provenance:

Private Collection, Salzburg, since the early 1930s

TEXT BY JANE KALLIR

© Jane Kallir

EGON SCHIELE’S LAST YEARS, 1917-18

In early 1917, Egon Schiele returned to Vienna from Mühling, the rural outpost where he had been stationed with the Austrian Army. During the preceding year of military service, he had produced relatively little art, but now he approached his career with renewed vigor. He rapidly reestablished and expanded his art-world contacts, fostering a relationship with the young director of the Staatsgalerie, Franz Martin Haberditzl, that led to a portrait commission (Kallir P. 309) and, in 1918, to the museum’s acquisition of the oil Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, Seated (Kallir P. 316). The publication in mid-1917 of a portfolio of facsimile reproductions of Schiele drawings, accompanied by a set of postcards, introduced his work to a new, broader audience. The artist began receiving fan mail and unsolicited inquiries from collectors, editors and writers. Exhibition activities picked up the pace, and Schiele was often asked not just to participate, but to organize these ventures. For the first time, he could afford to hire a contingent of professional models. By 1918, he also needed a secretary.

In keeping with his burgeoning professional life, Schiele created a large number of drawings in the last two years of his life: studies for portrait commissions and studies of various models. His 1917-18 style diverged sharply from the Expressionist idiom that had characterized his work prior to his induction into the army in 1915. The solipsistic self-absorption of late adolescence had been tempered by the artist’s marriage, also in 1915, to Edith Harms and by his empathy for the prisoners of war whom he encountered as a soldier. Complementing this more humanistic approach, Schiele’s drawings had become far more conventionally realistic. The contours hewed almost exclusively to the requirements of representational accuracy, with little latitude for expressive deviation. His palette was more subdued and naturalistic. A thin brownish under-glaze defined the principal volumes, and bolder dabs of color were used to highlight inflection points such as elbows, knuckles or lips. More opaque solids (stockings or hair) set off luminous drapery and flesh.

Overall Schiele was less concerned with color than with volume and shape, and increasingly he was driven to explore his subjects through drawing alone.

In 1917, for the first time in his brief life, Egon Schiele had access to a great many models. He was no longer compelled to enlist family, friends and girlfriends, but could afford to hire a changing retinue of professionals. Unsurprisingly, Edith Schiele objected, jealous of the naked women who populated her husband’s studio. But while she wanted to be his only model, this demand was complicated by Edith’s reluctance to pose nude. To assuage her embarrassment, Egon promised to alter her features so that she would not be recognized. And this may be one reason why the artist’s wife can be conclusively identified in relatively few of his more erotic works.

Edith’s jealously notwithstanding, she was clearly not Schiele’s only, or indeed even his principal model in 1917. In addition to a large contingent of professionals, Edith’s sister Adele Harms proved more than willing to pose. Like Edith, Adele seems seldom to have stripped completely. When not fully clothed, both sisters are usually depicted in flimsy chemises. In Schiele’s conventional portraits of the sisters, their faces are readily distinguished: Edith has more delicate features and a wistful sweetness; Adele’s visage is square-jawed and coarser. However, Adele is no easier to identify than Edith in the artist’s figure studies.

Schiele’s formal portraits of women had become far more incisive since his marriage in 1915, but his depictions of the nude or semi-nude female had grown more impersonal. The latter drawings were often intended as studies for allegorical paintings. As such, the artist was less interested in faces than in poses. His stylized simplification of facial features can make it difficult to distinguish the subjects of his figure drawings. Further complicating matters, in the case of Adele and Edith, is their family resemblance, and the fact that Schiele was not always accurate in his replication of telling details. (Adele had dark hair, while Edith was blond, but either might be depicted with reddish tresses.)

For all the foregoing reasons, it is impossible to conclusively identify the subject of Liegende Frau. Her facial features look somewhat like those of both Adele and Edith. She might be either sister, or neither. A similar face appears in several other works from the period (see Kallir D. 1977-80).

|

Horká linka kupujících

Po-Pá: 10.00 - 17.00

kundendienst@dorotheum.at +43 1 515 60 200 |

| Aukce: | Moderní |

| Typ aukce: | Salónní aukce |

| Datum: | 21.11.2017 - 18:00 |

| Místo konání aukce: | Wien | Palais Dorotheum |

| Prohlídka: | 11.11. - 21.11.2017 |

** Kupní cena vč. poplatku kupujícího a DPH

Není již možné podávat příkazy ke koupi přes internet. Aukce se právě připravuje resp. byla již uskutečněna.

Všechny objekty umělce